The Ambitious Quest for a Tunnel Under the Strait of Gibraltar

03/10/23-FR-English-NL-footer

03/10/23-FR-English-NL-footer

La quête ambitieuse d’un tunnel sous le détroit de Gibraltar

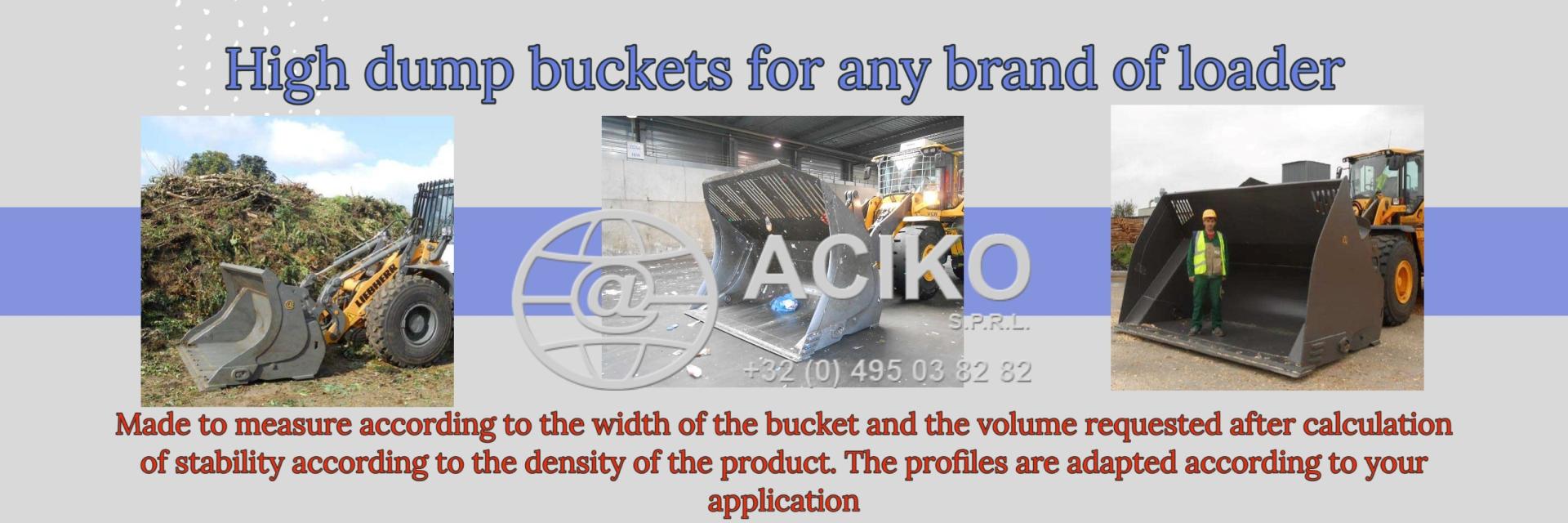

Image- ANGDavis Associates

Image- ANGDavis Associates

Dans une révélation sismique, les géologues ont proposé que la mer Méditerranée était autrefois un vaste lac fermé, sans issue apparente à l’est ou à l’ouest. Cependant, les forces incessantes des mouvements des plaques tectoniques et d’autres phénomènes naturels ont progressivement remodelé les contours du continent. Initialement, la Méditerranée s'est rétrécie à l'est, avant qu'une mystérieuse transformation géologique ne conduise à la formation du détroit de Gibraltar, une voie navigable étroite qui ne s'étend que sur 13 kilomètres.

Les résidents des côtes sud espagnoles et portugaises, ainsi que des côtes nord marocaines, peuvent se voir sur cette étendue relativement étroite. Au total, près de 90 millions de personnes habitent cette région. Étonnamment, l’idée de relier les États et les continents via un pont ou un tunnel a longtemps été une perspective alléchante, mais elle est restée lettre morte pendant des décennies.

Cependant, récemment, l’Espagne et le Maroc ont ravivé leurs plans pour cette entreprise colossale, envisageant un passage surnommé « détroit de canal de Gibraltar ».

Le détroit de Gibraltar, qui relie la mer Méditerranée à l'océan Atlantique, se situe entre la pointe la plus méridionale de l'Espagne et le nord-ouest de l'Afrique de l'Ouest. Il navigue dans les eaux territoriales du Maroc, de l'Espagne et du territoire britannique d'outre-mer de Gibraltar. S'étendant sur 36 milles, le détroit se rétrécit à seulement huit milles à son point le plus étroit, situé entre Point Morocci en Espagne et Point Ceres au Maroc. Des ferries sillonnent cette voie navigable quotidiennement, effectuant la traversée en aussi peu que 35 minutes.

À première vue, l’idée de construire une structure sur un plan d’eau de 13 kilomètres peut paraître anodine au regard des merveilles de l’ingénierie moderne. Prenons par exemple le pont récemment inauguré reliant la Russie et la péninsule de Crimée, long de près de 20 kilomètres. En Chine, de multiples ponts s'étendent sur des distances supérieures à 40 kilomètres. Le plus long pont sur l'eau existant au monde, le pont Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao, mesure 56 kilomètres.

Alors pourquoi un pont entre l’Europe et l’Afrique ne s’est-il pas concrétisé ? Est-ce un manque de prouesses techniques ou de ressources financières ? La réponse, paradoxalement, est à la fois oui et non.

Le rêve de relier les côtes africaines et européennes est né au milieu du XIXe siècle, à une époque où le chemin de fer devenait rapidement un mode de transport dominant pour les personnes et les marchandises. À un moment donné, il a même été proposé de construire un barrage et de bloquer entièrement le détroit de Gibraltar pour faciliter le transport. Heureusement, les ressources nécessaires n’étaient pas disponibles à cette époque.

Alors que des ingénieurs visionnaires entretenaient périodiquement le rêve, il a fallu plus d’un siècle pour que le projet reprenne son élan. En juin 1979, la Déclaration commune hispano-marocaine de Fès est signée par les rois d'Espagne et du Maroc pour faciliter la traversée entre l'Europe et l'Afrique. En 1988, le roi du Maroc a exprimé l'espoir que le pont serait achevé de son vivant, mais ces espoirs sont restés lettre morte.

Au fil des années, plusieurs ingénieurs ont conçu diverses propositions de ponts et de tunnels, chacun avec son propre tracé et sa propre configuration structurelle. Par exemple, une proposition du professeur T.Y. Lynn présentait un pont de 14 kilomètres de long avec des tours de 910 mètres de haut et une travée de 5 000 mètres, soit plus du double de la longueur de la plus longue travée de pont existante. En 2004, l'architecte Eugène Sui a proposé un pont flottant et immergé relié à une île de la mer Méditerranée. Cependant, la construction d’un pont a finalement été jugée impossible.

En décembre 2003, l'Espagne et le Maroc ont envisagé la construction d'un tunnel ferroviaire sous-marin traversant le détroit. Pourtant, les ingénieurs se sont heurtés à un obstacle majeur lorsqu’ils ont découvert des roches extrêmement dures sous le détroit, rendant le creusement de tunnels traditionnel impossible avec la technologie disponible. Une solution proposée consistait à ancrer un tunnel en béton préfabriqué au fond du détroit à l’aide de câbles, mais les défis géologiques ont soulevé des doutes quant à sa viabilité.

Fin 2006, Lombardi Engineering, une société suisse d'ingénierie et de conception, a été chargée de rédiger un projet pour le tunnel ferroviaire. Les défis uniques comprenaient la plus grande profondeur du détroit par rapport à la Manche et la présence d'une faille géologique active, la faille transformée Açores-Gibraltar, qui coupe le détroit, provoquant une activité sismique. La profondeur du détroit, en particulier dans la région la plus étroite, présentait d’autres complications.

De plus, le projet de tunnel était aux prises avec la complexité des courants océaniques multidirectionnels, posant de formidables obstacles aux ingénieurs et aux experts en hydraulique tentant d’évaluer la durabilité de la structure. Ces problèmes ont aggravé la complexité de la construction et soulevé des doutes quant à sa faisabilité. En outre, le coût du projet était une préoccupation majeure, les premières estimations datant de 2007 prévoyant un coût total de construction de 5 milliards d’euros, qui, corrigé de l’inflation, dépasserait aujourd’hui les 7 milliards d’euros.

Cependant, des études récentes ont ravivé les espoirs quant à la faisabilité du tunnel. En février 2023, à la suite d'une réunion bilatérale de haut niveau entre l'Espagne et le Maroc, les deux gouvernements ont décidé de relancer le projet de tunnel ferroviaire sous-marin traversant le détroit de Gibraltar. La construction du projet devrait commencer en 2030. La ministre espagnole des Transports, Raquel Sánchez, a souligné que les deux pays sont déterminés à faire avancer le projet, en chantier depuis 1979. Ils ont déjà collaboré avec l'entreprise allemande Herrenknecht, le leader mondial. le plus grand fabricant de tunneliers, qui a exprimé sa confiance dans la construction des machines massives nécessaires au forage du sous-sol du détroit.

La quête ambitieuse d’un tunnel sous le détroit de Gibraltar

Le tunnel envisagé serait composé de trois segments : deux tunnels à voie unique et une galerie de service reliés entre eux par des passages transversaux espacés de 340 mètres. Au total, le tunnel s'étendrait sur près de 39 kilomètres, dont 11 kilomètres exclusivement souterrains et 27,8 kilomètres sous l'eau. La construction devrait durer 10 à 15 ans et nécessiter une main-d'œuvre importante. Ce projet ambitieux pourrait stimuler la croissance économique dans les régions proches du tunnel.

Le tunnel promet de rationaliser la circulation des personnes et des marchandises plus efficacement que le transport aérien ou maritime, ouvrant potentiellement de nouvelles voies commerciales entre l’Europe et l’Afrique. Cela pourrait permettre aux marchés européens d’accéder plus facilement au continent africain via le Maroc. En retour, le Maroc espère attirer davantage de touristes et d’investisseurs, ainsi qu’une opportunité de commercialiser plus efficacement ses produits agricoles en Europe et au Royaume-Uni. De plus, le tunnel pourrait servir de conduit pour un nouveau gazoduc entre le Maroc et l’Espagne, élargissant ainsi son utilité.

Malgré la complexité structurelle du projet et le scepticisme de certains experts, les progrès de l'ingénierie ne le rendent pas totalement invraisemblable. L'amélioration des relations entre l'Espagne et le Maroc, associée au potentiel d'augmentation des échanges commerciaux, en font l'un des projets d'infrastructure les plus importants sur la scène mondiale. Pour l’instant, le sort de cette entreprise colossale est en jeu, mais la perspective d’un pont entre l’Europe et l’Afrique pourrait remodeler l’avenir de deux continents.

NJC.© Info ANGDavis Associates

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

03/10/23-English

03/10/23-English

The Ambitious Quest for a Tunnel Under the Strait of Gibraltar

Image- ANGDavis Associates

Image- ANGDavis Associates

In a seismic revelation, geologists proposed that the Mediterranean Sea was once a vast, enclosed lake, with no apparent exit points in the east or west. However, the relentless forces of tectonic plate movements and other natural phenomena gradually reshaped the contours of the continent. Initially, the Mediterranean shrank in the east, before a mysterious geological transformation led to the formation of the Strait of Gibraltar, a narrow waterway spanning just 13 kilometres.

Residents of the Spanish and Portuguese southern coastlines, and the northern Moroccan coastlines can actually catch see each other across this relatively narrow expanse. In total, nearly 90 million people inhabit this region. Surprisingly, the notion of connecting both states and continents via a bridge or tunnel has long been a tantalizing prospect, yet it has remained unrealized for decades.

Recently, however, Spain and Morocco have rekindled their plans for this colossal endeavour, envisioning a passage dubbed the “Strait of Gibraltar Channel.”

The Strait of Gibraltar, which links the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean, lies between the southernmost tip of Spain and north-western West Africa. It navigates through the territorial waters of Morocco, Spain, and the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. Stretching for 36 miles, the strait narrows to a mere eight miles at its narrowest point, situated between Point Morocci in Spain and Point Ceres in Morocco. Ferries ply this waterway daily, making the crossing in as little as 35 minutes.

At first glance, the idea of building a structure over a 13-kilometer stretch of water may appear trivial in the realm of modern engineering marvels. Consider, for example, the recently inaugurated bridge connecting Russia and the Crimean Peninsula, spanning nearly 20 kilometres. In China, multiple bridges extend over distances exceeding 40 kilometres. The world’s longest existing bridge over water, the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge, measures a staggering 56 kilometres.

So why hasn’t a bridge between Europe and Africa materialized? Is it a lack of engineering prowess or financial resources? The answer, paradoxically, is both yes and no.

The dream of linking the African and European coastlines was conceived in the mid-19th century, a period when railways were rapidly emerging as a dominant mode of transportation for people and goods. At one point, there was even a proposal to construct a dam and block the Strait of Gibraltar entirely to facilitate transportation. Fortunately, the necessary resources were not available at that time.

While visionary engineers periodically kept the dream alive, it took more than a century for the project to regain momentum. In June 1979, the Common Hispanic-Moroccan Declaration of Fez was signed by the kings of Spain and Morocco to facilitate the crossing between Europe and Africa. In 1988, the Moroccan King expressed hope that the bridge would be completed within his lifetime, but these hopes remained unrealized.

Over the years, several engineers have designed various bridge and tunnel proposals, each with its own alignment and structural configuration. For instance, a proposal by Professor T.Y. Lynn featured a 14-kilometre-long bridge with 910-metre-tall towers and a 5,000-metre span, more than double the length of the longest existing bridge span. In 2004, architect Eugene Sui proposed a floating and submerged bridge connected to an island in the Mediterranean Sea. However, the construction of a bridge was ultimately ruled out as impossible.

In December 2003, Spain and Morocco explored the construction of an underwater rail tunnel across the strait. Yet, engineers encountered a major obstacle when they discovered extremely hard rock beneath the strait, making traditional tunnelling unfeasible with the available technology. One proposed solution involved anchoring a prefabricated concrete tunnel to the strait’s floor using cables, but geological challenges raised doubts about its viability.

In late 2006, Lombardi Engineering, a Swiss engineering and design firm, was tasked with drafting a design for the railway tunnel. The unique challenges included the greater depth of the strait compared to the English Channel and the presence of an active geological fault, the Azores-Gibraltar Transformed Fault, which intersects the strait, causing seismic activity. The strait’s depth, particularly in the narrowest region, presented further complications.

Additionally, the tunnel project grappled with the complexities of multi-directional ocean currents, posing formidable obstacles for engineers and hydraulic experts attempting to assess the structure’s durability. These issues compounded the construction’s complexity and raised doubts about its feasibility. Furthermore, the project’s cost was a significant concern, with early estimates from 2007 projecting a total construction cost of 5 billion euros, which, adjusted for inflation, would exceed 7 billion euros today.

However, recent studies have rekindled hopes for the tunnel’s feasibility. In February 2023, following a high-level bilateral meeting between Spain and Morocco, the two governments resolved to revive the project for an undersea railway tunnel across the Strait of Gibraltar. The project is slated to commence construction in 2030. Spain’s Minister of Transport, Raquel Sanchez, emphasized that both countries are committed to advancing the project, which has been in the works since 1979. They have already engaged with the German company Herrenknecht, the world’s largest manufacturer of tunnel boring machines, which has expressed confidence in building the massive machines required to drill through the strait’s subsoil.

The Ambitious Quest for a Tunnel Under the Strait of Gibraltar

The envisioned tunnel would consist of three segments: two single-track tunnels and a service gallery interconnected by transversal passages spaced 340 meters apart. In total, the tunnel would span nearly 39 kilometres, with 11 kilometres exclusively underground and 27.8 kilometres underwater. Construction is anticipated to span 10 to 15 years and involve a substantial workforce. This ambitious project could stimulate economic growth in the regions proximate to the tunnel.

The tunnel promises to streamline the movement of people and goods more efficiently than air or sea transport, potentially opening up new avenues for trade between Europe and Africa. It could provide European markets with easier access to the African continent through Morocco. In turn, Morocco hopes to attract more tourists and investors, along with an opportunity to market its agricultural products more effectively in Europe and the UK. Additionally, the tunnel could serve as a conduit for a new gas pipeline between Morocco and Spain, expanding its utility.

Despite the structural complexity of the project and scepticism from some experts, advancements in engineering make it not entirely implausible. The improved relations between Spain and Morocco, coupled with the potential for increased trade, render this one of the most significant infrastructure projects on the global stage. As of now, the fate of this colossal undertaking hangs in the balance, but the prospect of a bridge between Europe and Africa could reshape the future of two continents.

NJC.© Info ANGDavis Associates

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

03/10/23-NL

03/10/23-NL

De ambitieuze zoektocht naar een tunnel onder de Straat van Gibraltar

Image- ANGDavis Associates

Image- ANGDavis Associates

In een seismische onthulling stelden geologen voor dat de Middellandse Zee ooit een uitgestrekt, omsloten meer was, zonder duidelijke uitgangspunten in het oosten of westen. De meedogenloze krachten van tektonische plaatbewegingen en andere natuurverschijnselen veranderden echter geleidelijk de contouren van het continent. Aanvankelijk kromp de Middellandse Zee in het oosten, voordat een mysterieuze geologische transformatie leidde tot de vorming van de Straat van Gibraltar, een smalle waterweg van slechts 13 kilometer.

Inwoners van de Spaanse en Portugese zuidelijke kustlijnen en de noordelijke Marokkaanse kustlijnen kunnen elkaar daadwerkelijk zien over deze relatief smalle uitgestrektheid. In totaal wonen er bijna 90 miljoen mensen in deze regio. Verrassend genoeg is het idee om staten en continenten met elkaar te verbinden via een brug of tunnel lange tijd een verleidelijk vooruitzicht geweest, maar toch tientallen jaren lang niet gerealiseerd.

Onlangs hebben Spanje en Marokko echter hun plannen voor deze kolossale onderneming nieuw leven ingeblazen, waarbij ze een doorgang voor ogen hadden die het ‘Straat van Gibraltar Kanaal’ wordt genoemd.

De Straat van Gibraltar, die de Middellandse Zee met de Atlantische Oceaan verbindt, ligt tussen het zuidelijkste puntje van Spanje en Noordwest-West-Afrika. Het vaart door de territoriale wateren van Marokko, Spanje en het Britse overzeese gebied Gibraltar. De zeestraat strekt zich uit over 36 mijl en versmalt tot slechts 13 kilometer op het smalste punt, gelegen tussen Point Morocci in Spanje en Point Ceres in Marokko. Veerboten varen dagelijks over deze waterweg en maken de overtocht in slechts 35 minuten.

Op het eerste gezicht lijkt het idee om een constructie te bouwen over een 13 kilometer lange waterstrook triviaal op het gebied van moderne technische wonderen. Neem bijvoorbeeld de onlangs ingehuldigde brug die Rusland en het Krim-schiereiland met een lengte van bijna twintig kilometer verbindt. In China strekken meerdere bruggen zich uit over afstanden van meer dan 40 kilometer. De langste bestaande brug ter wereld over water, de Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao-brug, meet maar liefst 56 kilometer.

Waarom is er dan nog geen brug tussen Europa en Afrika gerealiseerd? Is het een gebrek aan technische bekwaamheid of financiële middelen? Het antwoord is paradoxaal genoeg zowel ja als nee.

De droom om de Afrikaanse en Europese kustlijnen met elkaar te verbinden ontstond halverwege de 19e eeuw, een periode waarin de spoorwegen snel in opkomst waren als een dominant transportmiddel voor mensen en goederen. Op een gegeven moment was er zelfs een voorstel om een dam te bouwen en de Straat van Gibraltar volledig te blokkeren om het transport te vergemakkelijken. Gelukkig waren de benodigde middelen op dat moment nog niet aanwezig.

Terwijl visionaire ingenieurs de droom af en toe levend hielden, duurde het meer dan een eeuw voordat het project weer momentum kreeg. In juni 1979 werd de Gemeenschappelijke Spaans-Marokkaanse Verklaring van Fez ondertekend door de koningen van Spanje en Marokko om de oversteek tussen Europa en Afrika te vergemakkelijken. In 1988 sprak de Marokkaanse koning de hoop uit dat de brug binnen zijn leven voltooid zou worden, maar deze hoop bleef ongerealiseerd.

Door de jaren heen hebben verschillende ingenieurs verschillende brug- en tunnelvoorstellen ontworpen, elk met een eigen alignement en constructieve configuratie. Zo blijkt uit een voorstel van professor T.Y. Lynn had een 14 kilometer lange brug met 910 meter hoge torens en een overspanning van 5.000 meter, meer dan het dubbele van de lengte van de langste bestaande brugoverspanning. In 2004 stelde architect Eugene Sui een drijvende en ondergedompelde brug voor die verbonden was met een eiland in de Middellandse Zee. De bouw van een brug werd uiteindelijk echter als onmogelijk uitgesloten.

In december 2003 onderzochten Spanje en Marokko de aanleg van een onderwaterspoortunnel over de zeestraat. Toch stuitten ingenieurs op een groot obstakel toen ze extreem harde rotsen onder de zeestraat ontdekten, waardoor traditionele tunnelbouw onhaalbaar werd met de beschikbare technologie. Eén voorgestelde oplossing betrof het verankeren van een geprefabriceerde betonnen tunnel aan de vloer van de zeestraat met behulp van kabels, maar geologische uitdagingen deden twijfels rijzen over de haalbaarheid ervan.

Eind 2006 kreeg Lombardi Engineering, een Zwitsers ingenieurs- en ontwerpbureau, de opdracht een ontwerp te maken voor de spoortunnel. De unieke uitdagingen waren onder meer de grotere diepte van de zeestraat in vergelijking met het Engelse Kanaal en de aanwezigheid van een actieve geologische breuklijn, de Azoren-Gibraltar Transformed Fault, die de zeestraat doorsnijdt en seismische activiteit veroorzaakt. De diepte van de zeestraat, vooral in het smalste gebied, zorgde voor verdere complicaties.

Bovendien worstelde het tunnelproject met de complexiteit van multidirectionele oceaanstromingen, wat formidabele obstakels opleverde voor ingenieurs en hydraulische experts die probeerden de duurzaamheid van de constructie te beoordelen. Deze problemen verergerden de complexiteit van de constructie en deden twijfels rijzen over de haalbaarheid ervan. Bovendien waren de kosten van het project een groot probleem, waarbij volgens vroege schattingen uit 2007 de totale bouwkosten op 5 miljard euro zouden uitkomen, wat, gecorrigeerd voor inflatie, vandaag de dag meer dan 7 miljard euro zou bedragen.

Recente onderzoeken hebben echter de hoop op de haalbaarheid van de tunnel nieuw leven ingeblazen. In februari 2023, na een bilaterale ontmoeting op hoog niveau tussen Spanje en Marokko, besloten de twee regeringen het project voor een onderzeese spoortunnel over de Straat van Gibraltar nieuw leven in te blazen. De bouw van het project zal naar verwachting in 2030 beginnen. De Spaanse minister van Transport, Raquel Sanchez, benadrukte dat beide landen zich inzetten om het project, dat al sinds 1979 in de maak is, te bevorderen. Ze hebben al samengewerkt met het Duitse bedrijf Herrenknecht, 's werelds grootste bedrijf. grootste fabrikant van tunnelboormachines, die zijn vertrouwen heeft uitgesproken in de bouw van de enorme machines die nodig zijn om door de ondergrond van de zeestraat te boren.

De ambitieuze zoektocht naar een tunnel onder de Straat van Gibraltar

De beoogde tunnel zou uit drie segmenten bestaan: twee enkelsporige tunnels en een dienstgalerij die met elkaar zijn verbonden door dwarsdoorgangen op een afstand van 340 meter van elkaar. In totaal zou de tunnel bijna 39 kilometer lang zijn, waarvan 11 kilometer uitsluitend ondergronds en 27,8 kilometer onder water. De bouw zal naar verwachting 10 tot 15 jaar duren en er zal een aanzienlijk personeelsbestand bij betrokken zijn. Dit ambitieuze project zou de economische groei in de regio's in de buurt van de tunnel kunnen stimuleren.

De tunnel belooft het verkeer van mensen en goederen efficiënter te stroomlijnen dan lucht- of zeevervoer, waardoor mogelijk nieuwe wegen worden geopend voor de handel tussen Europa en Afrika. Het zou de Europese markten via Marokko gemakkelijker toegang tot het Afrikaanse continent kunnen bieden. Op zijn beurt hoopt Marokko meer toeristen en investeerders aan te trekken, samen met een kans om zijn landbouwproducten effectiever op de markt te brengen in Europa en Groot-Brittannië. Bovendien zou de tunnel kunnen dienen als kanaal voor een nieuwe gaspijpleiding tussen Marokko en Spanje, waardoor de bruikbaarheid ervan wordt uitgebreid.

Ondanks de structurele complexiteit van het project en het scepticisme van sommige experts, maken de vooruitgang in de techniek het niet geheel ongeloofwaardig. De verbeterde betrekkingen tussen Spanje en Marokko, gekoppeld aan het potentieel voor meer handel, maken dit tot een van de belangrijkste infrastructuurprojecten op het wereldtoneel. Op dit moment staat het lot van deze kolossale onderneming op het spel, maar het vooruitzicht van een brug tussen Europa en Afrika zou de toekomst van twee continenten opnieuw vorm kunnen geven.

NJC.© Info ANGDavis Associates

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Date de dernière mise à jour : 02/10/2023