Turning Carbon Dioxide into solid minerals underground

09/11/22-FR-English-NL-footer

Transformer le dioxyde de carbone en minéraux solides sous terre

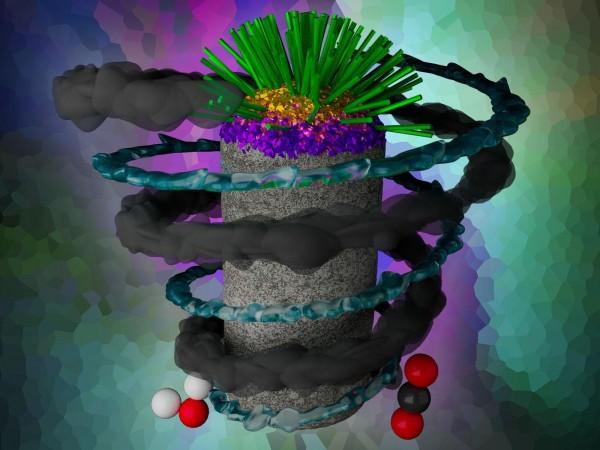

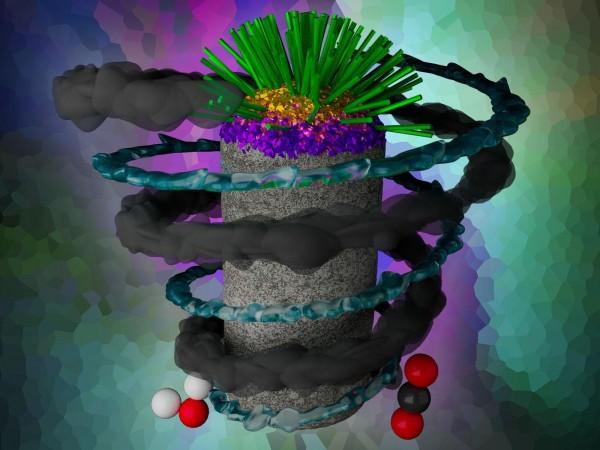

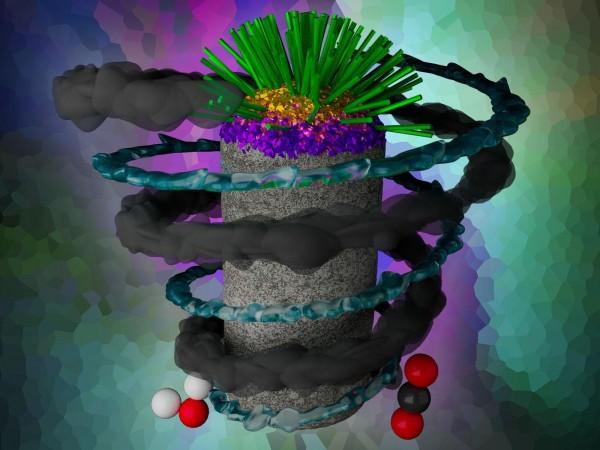

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Un nouvel article de revue scientifique de haut niveau dans Nature Reviews Chemistry explique comment le dioxyde de carbone (CO2) se transforme d'un gaz en un solide dans des films d'eau ultraminces sur les surfaces rocheuses souterraines. Ces minéraux solides, appelés carbonates, sont à la fois stables et communs.

"Alors que les températures mondiales augmentent, l'urgence de trouver des moyens de stocker le carbone augmente également", a déclaré Kevin Rosso, membre du laboratoire et co-auteur du Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). "En jetant un regard critique sur notre compréhension actuelle des processus de minéralisation du carbone, nous pouvons trouver les lacunes essentielles à résoudre pour la prochaine décennie de travail."

La minéralisation souterraine représente un moyen de garder le CO2 enfermé, incapable de s'échapper dans l'air. Mais les chercheurs doivent d'abord savoir comment cela se passe avant de pouvoir prédire et contrôler la formation de carbonate dans des systèmes réalistes.

"L'atténuation des émissions humaines nécessite de comprendre fondamentalement comment stocker le carbone", a déclaré le chimiste du PNNL Quin Miller, co-auteur principal de la revue scientifique présentée sur la couverture de la revue. "Il y a un besoin pressant d'intégrer des simulations, de la théorie et des expériences pour explorer les problèmes de carbonatation minérale."

Au lieu d'émettre du CO2 dans l'air, une option consiste à le pomper dans le sol. Mettre du CO2 profondément sous terre séquestre théoriquement le carbone. Cependant, les fuites de gaz restent préoccupantes. Mais si ce gaz CO2 pouvait être pompé dans des roches riches en métaux comme le magnésium et le fer, le CO2 pourrait être transformé en minéraux carbonatés stables et communs. Le Projet Pilote Basalte du PNNL à Wallula est un site de terrain dédié à l'étude du stockage du CO2 dans les carbonates.

Bien que ces environnements souterrains soient généralement dominés par l'eau, la conversion du dioxyde de carbone gazeux en carbonate solide peut également se produire lorsque le CO2 injecté déplace cette eau, créant des films extrêmement minces d'eau résiduelle en contact avec les roches. Mais ces systèmes très confinés se comportent différemment du CO2 au contact d'une nappe d'eau.

Dans les couches minces, le rapport de l'eau et du CO2 contrôle la réaction. De petites quantités de métal s'échappent des roches, réagissant à la fois dans le film et à la surface de la roche. Cela conduit à la création de nouveaux matériaux carbonatés.

Des travaux antérieurs dirigés par Miller, résumés dans la revue, ont montré que le magnésium se comporte de la même manière que le calcium dans les films d'eau minces. La nature du film d'eau joue un rôle central dans la réaction du système.

Comprendre comment et quand ces carbonates se forment nécessite une combinaison d'expériences en laboratoire et d'études de modélisation théoriques. Le travail en laboratoire permet aux chercheurs d'ajuster le rapport eau/CO2 et d'observer la formation de carbonates en temps réel. Les équipes peuvent voir quels produits chimiques spécifiques sont présents à différents moments, fournissant des informations essentielles sur les voies de réaction.

Cependant, le travail en laboratoire a ses limites. Les chercheurs ne peuvent pas observer les molécules individuelles ou voir comment elles interagissent. Les modèles chimiques peuvent combler cette lacune en prédisant comment les molécules se déplacent avec des détails exquis, donnant une base conceptuelle aux expériences. Ils permettent également aux chercheurs d'étudier la minéralisation dans des conditions difficilement accessibles expérimentalement.

"Il existe d'importantes synergies entre les modèles et les études en laboratoire ou sur le terrain", a déclaré MJ Qomi, professeur à l'Université de Californie à Irvine et co-auteur principal de l'article. "Les données expérimentales fondent les modèles dans la réalité, tandis que les modèles fournissent un aperçu plus approfondi des expériences." Qomi collabore avec l'équipe du PNNL depuis trois ans. Il a récemment reçu un prix du programme de recherche en début de carrière du Département de l'énergie pour étudier la minéralisation des carbonates dans les films d'eau adsorbés.

De la science fondamentale aux solutions

L'équipe a souligné les questions clés auxquelles il faut répondre pour rendre cette forme de stockage du carbone pratique. Les chercheurs doivent développer des connaissances sur la façon dont les minéraux réagissent dans différentes conditions, en particulier dans des conditions qui imitent de vrais sites de stockage, y compris dans des films d'eau ultrafins. Tout cela devrait être fait grâce à une combinaison intégrée de modélisation et d'expériences en laboratoire.

La minéralisation a le potentiel de garder le carbone stocké en toute sécurité sous terre. Savoir comment le CO2 réagira avec différents minéraux peut aider à s'assurer que ce qui est pompé sous la surface y reste. Les connaissances scientifiques fondamentales issues des travaux de minéralisation peuvent conduire à des systèmes pratiques de stockage du CO2. Le projet pilote Basalte représente un site d'étude important qui relie la science fondamentale à petite échelle et les applications de recherche à grande échelle.

"Ce travail combine un accent sur les connaissances géochimiques fondamentales avec un objectif de résolution de problèmes cruciaux", a déclaré Miller. "Sans donner la priorité aux technologies de décarbonisation, le monde continuera de se réchauffer à un degré que l'humanité ne peut pas se permettre."

Miller, Rosso et Todd Schaef étaient les auteurs PNNL de cette étude. Ce travail a été réalisé en collaboration avec MJ Qomi et Siavash Zare de l'Université de Californie à Irvine ainsi que John Kaszuba de l'Université du Wyoming. La recherche a été financée par le Bureau des sciences du Département de l'énergie (Programme des sciences de l'énergie de base) et le Bureau de l'énergie fossile et de la gestion du carbone (Partenariat pour le stockage et l'utilisation du carbone) ; la chaire du centenaire John et Jane Wold en énergie; et la bourse Nielson Energy.

NJC.© Info Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

09/11/22-English

Turning Carbon Dioxide into solid minerals underground

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

A new high-profile scientific review article in Nature Reviews Chemistry discusses how carbon dioxide (CO2) converts from a gas to a solid in ultrathin films of water on underground rock surfaces. These solid minerals, known as carbonates, are both stable and common.

“As global temperatures increase, so does the urgency to find ways to store carbon,” said Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Lab Fellow and coauthor Kevin Rosso. “By taking a critical look at our current understanding of carbon mineralization processes, we can find the essential-to-solve gaps for the next decade of work.”

Mineralization underground represents one way to keep CO2 locked away, unable to escape back into the air. But researchers first need to know how it happens before they can predict and control carbonate formation in realistic systems.

“Mitigating human emissions requires fundamentally understanding how to store carbon,” said PNNL chemist Quin Miller, co-lead author of the scientific review featured on the journal cover. “There is a pressing need to integrate simulations, theory, and experiments to explore mineral carbonation problems.”

Instead of emitting CO2 into the air, one option is to pump it into the ground. Putting CO2 deep underground theoretically sequesters the carbon away. However, gas leaks remain a concern. But if that CO2 gas could be pumped into rocks rich in metals like magnesium and iron, the CO2 can be transformed into stable and common carbonate minerals. PNNL’s Basalt Pilot Project at Wallula is a field site dedicated to studying CO2 storage in carbonates.

Although these subsurface environments are generally dominated by water, the conversion of gaseous carbon dioxide to solid carbonate can also occur when injected CO2 displaces that water, creating extremely thin films of residual water in contact with rocks. But these highly confined systems behave differently than CO2 in contact with a pool of water.

In thin films, the ratio of water and CO2 controls the reaction. Small amounts of metal leach out from the rocks, reacting both in the film and on the rock surface. This leads to the creation of new carbonate materials.

Previous work led by Miller, summarized in the review, showed that magnesium behaves similarly to calcium in thin water films. The nature of the water film plays a central role in how the system reacts.

Understanding how and when these carbonates form requires a combination of laboratory experiments and theoretical modelling studies. Laboratory work allows researchers to tune the ratio of water to CO2 and watch carbonates form in real time. Teams can see what specific chemicals are present at different points in time, providing essential information about reaction pathways.

However, laboratory-based work has its limits. Researchers cannot observe individual molecules or see how they interact. Chemistry models can fill in that gap by predicting how molecules move in exquisite detail, giving conceptual backbone to experiments. They also allow researchers to study mineralization in hard to experimentally access conditions.

“There are important synergies between models and laboratory or field studies,” said MJ Qomi, a professor at the University of California, Irvine and co-lead author of the article. “Experimental data grounds models in reality, while models provide a deeper level of insight into experiments.” Qomi has collaborated with the PNNL team for three years. He recently received a Department of Energy Early Career Research Program award to study carbonate mineralization in adsorbed water films.

From fundamental science to solutions

The team outlined key questions that need answering to make this form of carbon storage practical. Researchers must develop knowledge of how minerals react under different conditions, particularly in conditions that mimic real storage sites, including in ultrathin water films. This should all be done through an integrated combination of modeling and laboratory experiments.

Mineralization has the potential to keep carbon safely stored underground. Knowing how CO2 will react with different minerals can help make sure that what gets pumped underneath the surface stays there. The fundamental science insights from mineralization work can lead to practical CO2 storage systems. The Basalt Pilot Project represents an important study site that bridges small-scale basic science and large-scale research applications.

“This work combines a focus on fundamental geochemical insights with a goal of solving crucial problems,” said Miller. “Without prioritizing decarbonization technologies, the world will continue warming to a degree humanity cannot afford.”

Miller, Rosso, and Todd Schaef were the PNNL authors of this study. This work was performed in collaboration with MJ Qomi and Siavash Zare of the University of California, Irvine as well as John Kaszuba of the University of Wyoming. The research was supported with funding from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science (Basic Energy Sciences Program) and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (Carbon Storage and Utilization Partnership); the John and Jane Wold Centennial Chair in Energy; and the Nielson Energy Fellowship.

NJC.© Info Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

09/11/22-NL

Kooldioxide omzetten in vaste mineralen ondergronds

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Image- Mineralizing carbon dioxide underground is a potential carbon storage method. Credit: Illustration by Cortland Johnson | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Een nieuw spraakmakend wetenschappelijk overzichtsartikel in Nature Reviews Chemistry bespreekt hoe koolstofdioxide (CO2) van een gas in een vaste stof wordt omgezet in ultradunne waterfilms op ondergrondse rotsoppervlakken. Deze vaste mineralen, bekend als carbonaten, zijn zowel stabiel als algemeen.

"Naarmate de wereldwijde temperaturen stijgen, neemt ook de urgentie toe om manieren te vinden om koolstof op te slaan", zegt Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Lab Fellow en co-auteur Kevin Rosso. "Door kritisch te kijken naar ons huidige begrip van koolstofmineralisatieprocessen, kunnen we de essentiële hiaten voor het volgende decennium van werk vinden."

Ondergrondse mineralisatie is een manier om CO2 opgesloten te houden, niet in staat om terug in de lucht te ontsnappen. Maar onderzoekers moeten eerst weten hoe het gebeurt voordat ze carbonaatvorming in realistische systemen kunnen voorspellen en beheersen.

"Om menselijke emissies te verminderen, moet fundamenteel worden begrepen hoe koolstof moet worden opgeslagen", zegt PNNL-chemicus Quin Miller, co-hoofdauteur van de wetenschappelijke recensie op de omslag van het tijdschrift. "Er is een dringende behoefte om simulaties, theorie en experimenten te integreren om problemen met minerale carbonatatie te onderzoeken."

In plaats van CO2 uit te stoten in de lucht, is een optie om het in de grond te pompen. Door CO2 diep onder de grond te zetten, wordt de koolstof theoretisch vastgelegd. Gaslekken blijven echter een punt van zorg. Maar als dat CO2-gas zou kunnen worden gepompt in gesteenten die rijk zijn aan metalen zoals magnesium en ijzer, kan de CO2 worden omgezet in stabiele en gewone carbonaatmineralen. PNNL's Basalt Pilot Project in Wallula is een veldlocatie gewijd aan het bestuderen van CO2-opslag in carbonaten.

Hoewel deze ondergrondse omgevingen over het algemeen worden gedomineerd door water, kan de omzetting van gasvormig kooldioxide in vast carbonaat ook plaatsvinden wanneer geïnjecteerd CO2 dat water verdringt, waardoor extreem dunne films van restwater in contact met rotsen ontstaan. Maar deze zeer beperkte systemen gedragen zich anders dan CO2 in contact met een plas water.

In dunne films regelt de verhouding van water en CO2 de reactie. Kleine hoeveelheden metaal logen uit de rotsen en reageren zowel in de film als op het rotsoppervlak. Dit leidt tot de creatie van nieuwe carbonaatmaterialen.

Eerder werk onder leiding van Miller, samengevat in de review, toonde aan dat magnesium zich op dezelfde manier gedraagt als calcium in dunne waterfilms. De aard van de waterfilm speelt een centrale rol in hoe het systeem reageert.

Om te begrijpen hoe en wanneer deze carbonaten ontstaan, is een combinatie van laboratoriumexperimenten en theoretische modelleringsstudies vereist. Laboratoriumwerk stelt onderzoekers in staat om de verhouding van water tot CO2 af te stemmen en de vorming van carbonaten in realtime te bekijken. Teams kunnen zien welke specifieke chemicaliën op verschillende tijdstippen aanwezig zijn, waardoor essentiële informatie over reactiepaden wordt verstrekt.

Laboratoriumwerk heeft echter zijn grenzen. Onderzoekers kunnen individuele moleculen niet observeren of zien hoe ze op elkaar inwerken. Chemische modellen kunnen die leemte opvullen door te voorspellen hoe moleculen tot in de kleinste details bewegen, waardoor experimenten een conceptuele ruggengraat vormen. Ze stellen onderzoekers ook in staat om mineralisatie te bestuderen in moeilijk te experimenteel toegankelijke omstandigheden.

"Er zijn belangrijke synergieën tussen modellen en laboratorium- of veldstudies", zegt MJ Qomi, een professor aan de University of California, Irvine en mede-hoofdauteur van het artikel. "Experimentele data baseert modellen in de werkelijkheid, terwijl modellen een dieper inzicht in experimenten bieden." Qomi werkt al drie jaar samen met het PNNL-team. Hij ontving onlangs een prijs van het Department of Energy Early Career Research Program om carbonaatmineralisatie in geadsorbeerde waterfilms te bestuderen.

Van fundamentele wetenschap naar oplossingen

Het team schetste belangrijke vragen die beantwoord moeten worden om deze vorm van koolstofopslag praktisch te maken. Onderzoekers moeten kennis ontwikkelen over hoe mineralen reageren onder verschillende omstandigheden, met name in omstandigheden die echte opslaglocaties nabootsen, ook in ultradunne waterfilms. Dit moet allemaal worden gedaan door een geïntegreerde combinatie van modellering en laboratoriumexperimenten.

Mineralisatie heeft het potentieel om koolstof veilig ondergronds te bewaren. Weten hoe CO2 zal reageren met verschillende mineralen kan ervoor zorgen dat wat onder het oppervlak wordt gepompt, daar blijft. De fundamentele wetenschappelijke inzichten uit mineralisatiewerk kunnen leiden tot praktische CO2-opslagsystemen. Het Basalt Pilot Project vormt een belangrijke onderzoekslocatie die een brug slaat tussen kleinschalige basiswetenschap en grootschalige onderzoekstoepassingen.

"Dit werk combineert een focus op fundamentele geochemische inzichten met het doel om cruciale problemen op te lossen", aldus Miller. "Zonder prioriteit te geven aan decarbonisatietechnologieën, zal de wereld blijven opwarmen tot een niveau dat de mensheid zich niet kan veroorloven."

Miller, Rosso en Todd Schaef waren de PNNL-auteurs van deze studie. Dit werk werd uitgevoerd in samenwerking met MJ Qomi en Siavash Zare van de University of California, Irvine en John Kaszuba van de University of Wyoming. Het onderzoek werd ondersteund met financiering van het Department of Energy's Office of Science (Basic Energy Sciences Program) en Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (Carbon Storage and Utilization Partnership); de John en Jane Wold Centennial Chair in Energy; en de Nielson Energy Fellowship.

NJC.© Info Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------